- Home

- Elissa Schappell

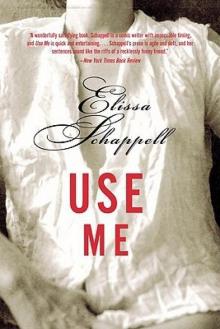

Use Me

Use Me Read online

Elissa Schappell

USE ME

In memory of my father,

Frederick Schappell

Contents

Eau-de-Vie

Novice Bitch

To Smoke Perchance to Dream

Use Me

The Garden of Eden

Sisters of the Sound

Wild Kingdom

Try an Outline

In Heaven, Dead Fathers Never Stop Dancing

Here Is Comfort, Take It

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher

EAU-DE-VIE

“Pouilly-Fumé, Chardonnay, Pouilly-Fuissé, Sancerre.” I chant my mantra in the backseat of our white rental car, Josephine, as we speed through the Loire Valley countryside, past chateaus and vineyards and endless rows of grapevines.

It’s not fair that all my friends get to be normal and go to the beach, and I have to go to France and be a total albino. I barely ever see the sun because my parents are constantly dragging me and Dee through every museum, church, and restaurant in France. We spent two whole days in the Louvre!

On the road I lean as much of my body out the window as I can without attracting my mother’s attention. At least today we’ll be outside, not during peak tanning hours, but God, I’ll take it. I love that feeling of sun soaking into my bones. My dad says the sun turns the grapes’ blood into sugar. “You can taste the sun in the grapes,” he says, “the way you can taste dirt in a tomato.”

Dad is speeding because we’re racing to make the tour of some vineyard where they produce a prized Pouilly-Fumé (whoop-de-do) and a brandy called Pear William (ditto the whoop-de-do). My mother has been dying to go to this château place ever since she “discovered” it in Gourmet magazine. You know, she showed me that picture three times before we left. Each time I saw the same thing: a bunch of pear trees with wine bottles roped to their branches, and inside each bottle a tiny pear was supposedly growing. I tried to make out the pears. I never could, but I guess a magazine wouldn’t lie about a thing like that.

My little sister is eating a yellow pear out of a handkerchief. My mother says that’s how the French eat them. Their skins are so soft they bruise brown when you touch them and rip open so easily they nearly dissolve in your mouth. Big deal. All I know is Dee is getting the whole backseat sticky and drawing flies. As far as I can tell, anything good draws flies.

Dee eats only fruit, bread and butter, and pommes frites. Oh, sure, she’ll say, “Yes please, yes please,” when my parents offer her poached salmon in béchamel sauce or foie gras on toast. Dee always says yes—she wouldn’t want to disappoint you—but Dee, she won’t eat one mouthful, and because she’s so cute, so small and blonde and pretty, with her big blue doll-baby eyes, she gets away with murder.

My dad’s going to put us into a ditch if he doesn’t slow down. It doesn’t help that he’s got his arm around my mother, who is wearing her Jackie O sunglasses and a black and purple silk scarf tied around her long blonde hair like a gypsy. I’m just thankful she’s not wearing her toe ring. I can’t wear an anklet because “it looks tacky,” but she can wear a toe ring. Explain that to me. She’s just showing off because she has feet like the statue of Venus de Milo. My dad pointed this out in the Louvre. “Look,” he said, dragging us over to inspect the goddess of love’s feet. “See, the second toe is slightly longer than the big toe, it’s perfection.”

He even made Mom take her shoe off in the museum and compare. She acted like she was embarrassed, you know—“Oh, Chas, honey, stop stop”—but she did it. For Dad. I bet she’s sorry now she didn’t pack that toe ring. It’s not like she’d need it. France is like Spanish fly to my parents. Ever since we got off the plane they’ve been pawing each other. More than usual. Which is saying something, believe me.

Dad looks mostly normal. His black hair is a little on the long side, but he’s dressed in a regular Levi’s denim work shirt, jeans, and the sneaks he wears to cut the grass. The only problem is that my father, who has shaved every day of his life, even on weekends, is now growing this horrible little black beard for my mother. With her head scarf and his beard, they look like pirates who’ve escaped the suburbs, taking me and Dee along as hostages. It doesn’t help that my dad is also wearing these black wraparound sunglasses that my mother bought at a gas station. I’ve never seen my dad in sunglasses. It’s creepy. I know he’s wearing shades in case we get pulled over for speeding, so the cop can’t see his eyes are all bloodshot from drinking wine at lunch. He also reeks of cigarettes because he and Mom smoked Gauloises after lunch. The thing is, my parents don’t even smoke!

“We’re getting close,” Dad says, and leans over to kiss my mother on the mouth. Josephine jerks to the right, and Dad accidentally flips on the windshield wipers for only about the hundredth time. He shouts, “Jesus Christ, I’d like to strangle the guy who engineered this car!”

Dad should have both hands on the wheel, seeing as how he drank almost a whole bottle of red wine at lunch. Mom had just half a glass, it gives her a headache. Red wine and frog’s legs, you can’t have one without the other, according to my father, who it seems has read every book about France ever written, so he must know best.

My dad is on a quest to cram culture into us, so we don’t have to pick it up late in life like he had to. See, Dad never went to Europe as a kid. It wasn’t just that Grandpa was a plumber and so there wasn’t lots of money for travel; the family never went anywhere, except to the lake, or hunting.

Dad says his father and mother never traveled because Grandpa was uneducated and feared the unknown. It was the same reason he forbade my grandmother to have a job or drive, and why my dad could never learn to ride a bike.

Of course, my dad, he felt he wasn’t doing his fatherly duty unless his little girls saw every pane of stained glass, every splinter of the One True Cross, every crappy druid stone formation, every scenic panoramic view, and anything that could be considered “art” in all of France. I don’t know which is worse. At least at a lake I could lay out.

At lunch today Dad offered to lend me his ratty old copy of A Vagabond’s Guide to Paris in the ’50s.

“I think you’ll like it. It’ll give you a sense of history. It’s cool,” he said as he sucked the meat off a tiny jointed frog drumstick. I thought I was going to pass out. You know, what the Fu Manchu happened to the rest of the frog? Was there a bucket of stump frogs in the kitchen, and if so, were they still alive and flopping around?

“Hmmm, chickeny,” Dad said. He smacked his lips. “I think you’d like this. Give it a try.”

“Frog? No, thank you.”

“How can frog taste like anything but frog?” Dee asked. She leaned down to pet one of the stray cats lurking under our table, living it up on all the food Dee “accidentally” dropped.

“Oh, come on. Be brave, puss, take a chance,” he said. He reached over to mess up my hair.

“Dad,” I said, for like the hundredth time, and swatted at his hand. I’d just spent all morning trying to de-frizz my hair. Unlike my mother, I didn’t go for the natural I-am-woman-hear-me-roar hair thing.

“Oh, sorry, sorry, the hair. I forgot, don’t touch the hair.” He let his hand rest on my shoulder for a second, like he didn’t know what to do with it.

“This is animal cruelty, Dad.”

“You know, Tommy Ford had rattlesnake once,” my mother said. “He said it tasted like chicken too. Same with emu.” She dove into a plate of escargots that the waiter insisted had been farmed from birth on parsley and thyme. My parents were eating so low on the food chain it was ridiculous; this stuff was like bait.

“Really? Gee, that’s too bad,” Dad said, sounding genuinel

y disappointed. “Listen, you never know, maybe to some people everything tastes like chicken.”

“Daddy, you just said frog tasted like chicken,” I reminded him. My mother had a fleck of parsley wedged between her teeth. I wanted to scream.

“Mom,” I said under my breath, “Clarissa.”

“What?”

“Clarissa,” I said louder this time. Clarissa was a family code word that meant you had food in your teeth.

It came from a girl I went to arts and crafts camp with named Clarissa, who always got food stuck in her braces. My mother sucked her teeth in this embarrassing way. “Gone?”

I nodded. Thank God. Sometimes just listening to her chew can make me feel I’m going insane.

“Is it so wrong for a father to want his children to try new things, to actually have a foreign experience? If so, sue me.”

“It doesn’t taste chickeny. You lied. I can’t believe you lied.”

“I’m not going to argue this with you, Evelyn, it’s ridiculous.” He slammed his hand down on the table so the bread jumped in its basket.

Man, was he ever getting riled up.

“What about the sweetbreads?”

“Grace, more wine?” he asked, ignoring me.

“Dad?”

He bit his lip like he was trying to control his temper.

“I told you right off the bat that sweetbreads were fried thymus.”

“Okay, but duh, who knows what a thymus is?”

“Then you, little lady, should have paid more attention in biology class. The point is, you liked them.”

“I hated them. The texture was all wrong, weird and spongy, and I’d never have known that’s what they were if I didn’t just happen, by mistake, to see in the guidebook that they were glands. Sex glands!”

Dad shrugged like it was no big deal. Like all the cool people went around eating sex glands.

“You didn’t tell me that,” I said.

“That’s right,” he said. “You would never have tried them. You don’t know what you could be missing, Evelyn.”

I had almost spit the sweetbreads out. I knew from the minute it touched my tongue that it was dirty, that a person would be crossing some line even having it in her mouth. But my father was looking at me like he was so proud, so I just swallowed it. I almost gagged. I bet giving somebody a blow job was disgusting like that. These thymus glands were responsible for creating sexuality in animals. I wondered if it was possible to have them removed, or if I could have mine checked out, without having to take my clothes off, if possible. I was a little afraid that I was way too sexed up. It seemed every boy that went by on a Vespa looked good to me, even the ones with acne and snaggleteeth, and that wasn’t right. Everybody that passed by, I thought, What about him? What about that one? Maybe something was wrong with me. Left alone for five minutes, I couldn’t keep my hands out of my pants. Not like I was doing anything, I just liked resting my hand there.

“So, are we going to be able to drink liquor at this place or what?” I call up to the front seat, even though I know it’s hopeless.

My parents both answer at the same time.

My mother says, “No, we’ll get you a soda, or an ice-cream cone if you’d like.”

Dad says, “We’ll see.”

This is as good as a yes, and I’m shocked. There’s a wonderful, disturbing quiet in the car; my parents rarely disagree about anything, ever. They are a team. Dee gives me a curious look. She’s still on edge from dinner last night, when my mother accused me of making eyes at a busboy. I didn’t mean to.

“You are never borrowing that dress again,” she said the minute he left the table. She was so angry, her hands were shaking as she tried to tug up the straps of the clingy black sundress. Was it my fault I filled it out better than her? Was it my fault she was as flat as two fried eggs? When she wore one of her slinky dresses she’d just slap Band-Aids over her nipples so they didn’t poke out like party hats.

“You said I could wear it.”

“You nearly caused a riot walking here, and I mean it, no more of that swishy walk—where did you pick that up? Have you been watching Marilyn Monroe movies, or some T-and-A Battle of the Network Stars thing, what? It’s so objectifying. Gloria Steinem would—”

Dee knocked over her milk glass. “Oops,” she said, but my mother barely batted an eye. I swear, Dee did this all the time, just for attention.

“What are you talking about?” I crossed my arms over my chest. I was starting to blush. I tried not to laugh—it wasn’t Suzanne Somers or Barbi Benton. It was just me.

“You know what I’m talking about, young lady. That walk will get you into trouble, so unlearn it now. It won’t always be cute boys on motorbikes whistling at you,” she said, grabbing my arm across the table, her nails digging into my skin. Since arriving in France three days ago she’d painted her nails red, much darker than any color I’d ever seen her wear at home, and had also started wearing a dark wine-colored lipstick that looked very chic, but forget about me telling her that now.

“Did you see the old guy offer me half his ham sandwich?”

“Yes, I did. Not to mention all those disgusting sucking noises they make, that makes me so mad. Who do they think they are treating women like that? Don’t laugh, Evelyn, it’s not funny. And it wouldn’t happen, Charles, if you walked with us, all together, like a family.”

“What?” my father said, looking up from the menu and wine list. He blinked his eyes like somebody was shining a flashlight in his face.

Dee said, “Daddy, I spilled my milk. See?” She pointed to her plate. A piece of fried fish and some carrots floated in a sea of milk.

“Dee, honey, watch your elbows, please,” he said, and tried to mop up the milk that had splashed onto her jumper. I thought he’d be mad, but he was perfectly cool.

My mother was just heating up. “I said, dear, on the way home she’s wearing your sport coat and you’ll walk on one side of her and I’ll walk on the other. Let’s see if we can get Miss Sexpot home in one piece.”

“Uh-oh,” Dee said, and slid down in her chair. “Somebody’s a sexpot.”

My father put down the napkin and focused on me. He hardly ever looked right at me anymore, it was like I was a stranger he didn’t want to get caught staring at.

“Listen to your mother, Evelyn, she knows what she’s talking about.”

“But, Daddy…” I was afraid I was going to crack up. It was none of their business in the first place.

“You heard me. Cut the crap.”

It was clear: now that I was fourteen I belonged to my mother.

I hated them both.

In the hotel room that night, while my mother was in the bath brushing her teeth and Dee was playing with her stuffed horse, Twinkle, I went over to where Dad was sitting at a desk, the map stretched out in front of him, planning our route to the winery. I wondered if he was mad at me. He hadn’t looked at me once during dinner. Walking back to the hotel, he’d given me his suit coat to wear, and he walked with us most of the way back, but I kept my head down, and he didn’t say much. Dee and Mom made up funny lyrics to “Frère Jacques” and sang all the way home. Every time my father got slightly ahead of us, my mother would call him back; each time it was like he forgot why he was supposed to be playing chaperon, then, remembering, his face would cloud up. He resented having to baby-sit me when he wanted to explore side streets, to go as he pleased. But my mother would have it no other way. By the time we got to the hotel I wanted to kill my mother.

We were all sleeping in one room that had two big beds. I brushed my teeth, got into my Snoopy nightshirt, and crawled into bed with A Vagabond’s Guide to Paris in the ’50s.

When my mother went into the bathroom to perform her nightly toilette, I got out of bed. I couldn’t help it. I couldn’t stand him being mad at me.

“Hi, Daddy,” I said, nudging my way into his lap.

“Oof,” he said as I sat down, like I was heavy.

&nb

sp; “Gee, thanks, Dad,” I said, then, “I’m sorry if I made you mad earlier.”

“What do you mean?” He looked confused, like he wasn’t sure exactly what I was talking about.

“You know,” I said.

“Ouch,” he said, and moved his legs so I was mostly on just his right knee. It wasn’t too comfortable, so I scooted closer, and fixed the hem of my nightshirt so it would stop riding up.

He frowned but didn’t say anything, and went back to studying the map. I waited for him to say something, to get mad, or put his arm around my waist, or hug me, or kiss my hair, but he didn’t. He just continued to look at the dumb map, tracing the road with a mechanical pencil.

“Daddy, rub my back,” I said, raising my shoulders up and down. “My back hurts.”

He acted like he didn’t hear me.

“Come on, please.”

He sighed, and without even looking at me, he clamped his hand onto the top of my shoulder and gave it one hard squeeze.

“Ouch, softer. That’s like a Vulcan death grip.” I laughed, leaning back closer to him, resting my back against his shoulder. “Come on, do more. Please.”

He sighed and once again squeezed the top of my shoulder in the same place, again too hard.

“Ouch, Dad…pay attention, yikes, it hurts.” I shook out my shoulders, then straightened up tall, like my back was now a clean slate to start over on. I was willing to forget.

“That’s it,” my father said, and started to stand up. So I had no choice but to get up too.

“Daddy,” I said.

“That’s it,” he said again. “It’s bedtime.”

“Are you going to keep that beard?”

He sort of laughed and stroked his face, like he’d forgotten it was there.

“No, I don’t think so.”

“Good.”

Use Me

Use Me